By Santhosh D’Souza. First Published on 29 Aug 2020

The National Health Authority (NHA) has released a draft of the National Digital Health Mission, NDHM’s Health Data Management Policy. The policy draft attempts to create a framework for the secure processing of personal and sensitive data of individuals, who are a part of the National Digital Health Ecosystem (NDHE).

One overarching question was that of creation of a Health ID. It was unclear why a separate Health ID is required at all. Was the Aadhaar Card not deemed the one mechanism of uniquely authenticating an individual across all citizen engagements?

The draft policy indicates that a Health ID can be generated only upon authentication using the Aadhaar Number, or any other identification documents (which are unspecified in the draft itself).

It might be worthwhile for the NHA to spell out what other documents of identification might suffice.

The draft policy does later mandate that a lack of the Aadhaar Number (or a mobile number) should not prevent a citizen from participating in the NDHE.

This would be the rationale for a separate Health ID then.

DATA CREATION

The problematic content of the draft centres on the nature of data collected.

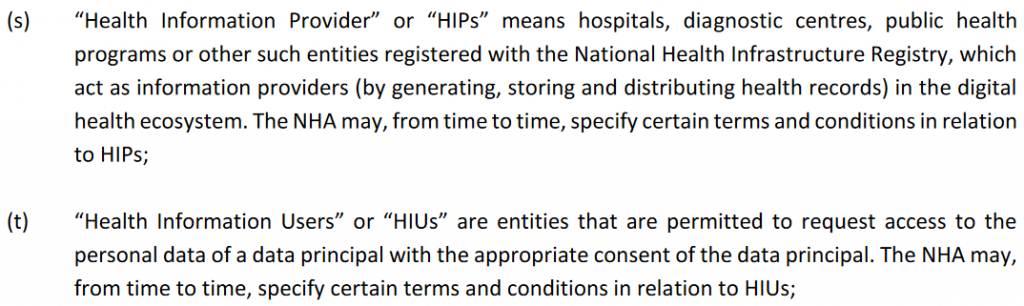

Data Fiduciaries are the principal data collectors:

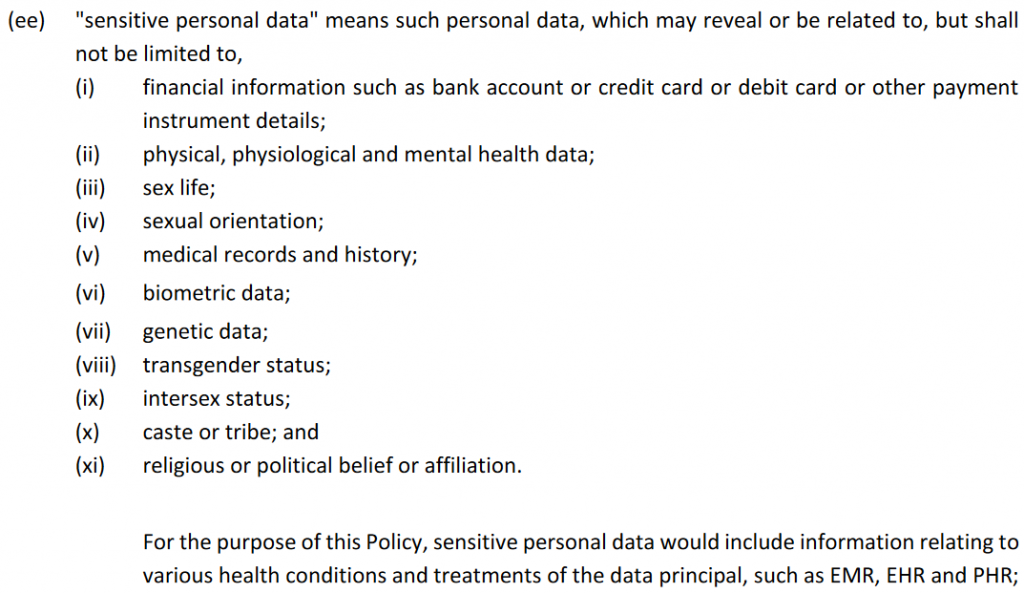

Personal or sensitive personal data is defined thus:

It is extraordinary that the Health Ecosystem will require the storage of data related to a citizen’s sex life, sexual orientation, caste/tribe and religious/political beliefs or affiliations. Possible scenarios requiring this data to be stored in the National Health Authority’s database are not elucidated anywhere in the draft policy.

A citizen’s sex life and sexual orientation might arguably have a bearing on the conversations between them and the medical practitioners they are consulting. This is quite easily addressed by the citizen actually discussing those details with the practitioner verbally. That the National Health Authority’s data platform should store these details is inexplicable.

The caste/tribe and religious/political beliefs/affiliations should be excluded entirely from this list – they have no relevance at all that requires them to be stored. If the National Health Authority argues that the nature of treatment or specific medications used might be influenced by these affiliations, then they can well be discussed between the citizen and the health practitioner themselves, with no need for their permanent storage.

The same questions might legitimately be raised on aspects like genetic data, transgender and intersex status.

Another question unaddressed by the draft policy is what implications the seeding of the Health ID with the Aadhaar Number might have. Does this mean that the data associated with the Aadhaar Number – financial transaction information for example – gets seeded in the Health Database as well? The policy does not explicitly mention a clear separation between the two information systems.

DATA ERASURE

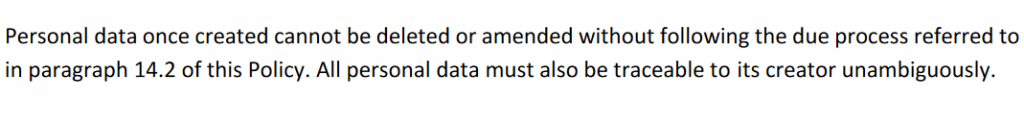

The next issue is with the section addressing erasure of the data. Note that the draft policy states that participating in the NDHE is entirely voluntary.

The policy states that data created cannot be changed or deleted except under the following conditions:

The draft seems to envision scenarios under which some law might mandate the preservation of the citizen’s data. It does not elaborate what law or laws these are, or whether such a law even exists today. This is problematic – it is difficult to imagine circumstances under which a citizen wishing to exit the NDHE should be forced to leave data behind. If entry into the NDHE is voluntary, the policy should assure the citizen that their exit would be accompanied by complete erasure of the data as well – to revert to a status quo ante as if the citizen had not entered the NDHE in the first place.

DATA SHARING

The policy outlines how the data might be shared:

While it states that Health Information Users can only obtain the data from the data fiduciary with the consent of the concerned citizen, it does not anywhere address the issue of how much (or how little) of the data can be shared in each transaction. This section seems to make it an “All or Nothing” transaction – either the citizen can refuse to share their information with the HIU or consents to sharing all of the data. If this is not the intention of the policy, it ought to make it clear in this section itself that the citizen can exert control over data sharing at a granular level.

In a subsequent section, the policy does guide for data minimization:

Unfortunately this principle is articulated in a section titled “Obligations of HIUs upon sharing of personal data” – almost as if the principle applies after all the data has already been shared by the data fiduciary with the HIU.

Disclaimer : The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. AlignIndia does not take any responsibility for the content of the article.

(Santhosh D’Souza combines professional interest in technology with a passion for science, history, mythology and current affairs. He tweets @santhoshd)