By Santhosh D’Souza

The Modi government has unveiled a bewildering melange of schemes since it first came to power in 2014. Ignoring the curious reliance on the Aadhar platform championed by the UPA government and severely criticized by Modi previously, virtually every single scheme itself has proven to be a damp squib. One of the earliest – the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (JDY) – is no different.

When launched on 28 August 2014, it was packaged as the advent of an unprecedented and bright financial future for the unbanked. Tellingly, the only statistics that Modi cited while hailing its sixth anniversary in 2020 were the overall counts – 40.35 crore accounts, the breakup of rural and urban, male and female account holders. There was nothing whatsoever on how these accounts benefited holders, how many are actively used, how many of them are the only bank account the individual holds, how the accounts when used seem to be exploited for various fraudulent practices… such details were omitted for good reason as we shall soon see.

Before we analyse the shortcomings in implementation, we should point out that the scheme itself was a re-branding of a UPA programme in existence for a decade.

The UPA’s Financial Inclusion Scheme

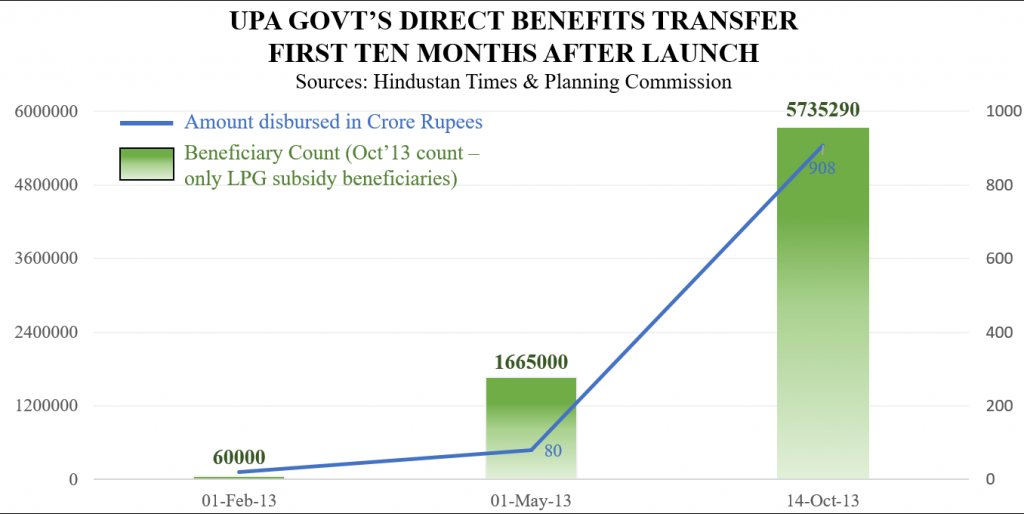

As P Chidambaram wrote in 2015, the UPA government had launched the No Frills or Zero Balance Account scheme (known formally as the Basic Savings Bank Deposit Account or BSBDA) as long ago as 2005. After a revision in strategy and implementation the base had grown to 24.3 crore accounts by March 2014. The Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) programme, again launched by the UPA government in January 2013 began with 60000 people across 20 districts receiving 20 crore rupees in the first month.

By the end of April that year, according to the Planning Commission, 16.65 lakh beneficiaries had been enrolled and over 80 crore rupees disbursed. LPG subsidies, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) and 23 other benefits were included in the next phase of the roll-out across 121 districts. By 14 October 2013, the amount disbursed through DBT stood at over 908 crore rupees (614 crore rupees of which LPG subsidies) through 1.6 crore transactions. The beneficiaries of the LPG subsidy alone added up to 57.35 lakh by then.

It ought to be clear to neutral observers why the pace of BSBDA and transaction volumes/deposit sizes since January 2013 far outstripped comparable statistics prior to 2013. As Geevarghese Vaidyan, Deputy Managing Director of State Bank of India explained, the financial inclusion target base in 2005, living as it did primarily in rural areas, was still handicapped by lack of connectivity. In 2013, the connectivity had improved beyond recognition. The other reason was that as benefits were transferred to recipients through other means, generally cash, it was not until the mechanism switched to depositing them in bank accounts that a demand for such accounts swelled.

It should not therefore surprise anyone that these two factors fuelled the same growth in the JDY statistics as they did for the BSBDA scheme prior to May 2014. What should appall everyone is the manner in which the Modi government tried to artificially inflate the statistics and the incompetent execution that led to abuse and misuse of the scheme.

Dubious Claims about the Benefits

The Modi government claimed that JDY was significantly different from equivalent schemes from the UPA period. This claim is primarily based on the insurance cover and the overdraft facility available under the new scheme.

The overdraft facility had a ceiling of Rs 5000 (subsequently raised to Rs 10000). Even this limited facility comes with further caveats –

- Account should have been Aadhaar-linked.

- Account needs to maintain a “healthy” positive balance for six months.

- Account holder should be making regular cash and debit card transactions in that period.

- Interest is charged on the overdraft.

Naturally, an infinitesimal percentage of JDY accounts benefit – As of 23 January 2019, 1.9% of the accounts were eligible for and only 0.9% were issued overdrafts. The average overdraft per account that availed of the facility was Rs 1135. By no standards can these statistics be cited as proof for the uniqueness of the JDY.

The Insurance Cover claim is also undermined by even more abysmal benefits – as of March 2019, 0.004% of account holders applied for insurance claims, and of these ludicrously low numbers, 78% of the claims were settled.

Equally hollow was Modi’s claim that DBT and JDY saved a sum of 90000 crore rupees by 2019. As this detailed analysis demonstrates, 98% of these alleged savings are attributed to three schemes – LPG subsidy, the Public Distribution System (PDS) and MGNREGS. Nearly 50% or 42275 crore rupees were apparently “saved” in the LPG Subsidy scheme.

The same analysis reveals the conclusion on these “savings” in 2016 by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) – 90% was due to the fall in global crude oil prices. Another 7.6% was due to reduced offtake of cylinders by beneficiaries. Neither DBT nor JDY had a significant role to play in the savings! As for PDS and MGNREGS “savings”, the government has no explanation for how it arrived at the figures, and the CAG cannot validate their veracity.

Issues with Jan Dham Yojana

Hard-pressed by the Modi government to prove that the JDY was a success, bankers took to a curious kind of fraud themselves. An Indian Express investigation in 2016 discovered large scale one rupee deposits across JDY accounts to eliminate zero balance accounts following criticism of the JDY. Across 34 public sector banks and subsidiaries, over a crore of JDY accounts had a single transaction executed – a deposit of one rupee. A lady in Bhopal found 10 paise in her dormant account. The pressure was so intense that several bank employees deposited their own money in these dormant accounts. Others creatively transferred money from various allowances and subsidies that bank employees were eligible for into their customers’ zero balance JDY accounts.

The other pressure the bankers were subjected to was naturally to open as many JDY accounts as possible. It is not surprising therefore to discover, as a May 2017 study did, that over 51% of the individuals (and 79% of the households) with a JDY account also had a non-JDY bank account. Many bank account holders were induced to open an account meant for the unbanked. To a certain extent this also explains why the same study found that 25% of JDY accounts still had zero balances.

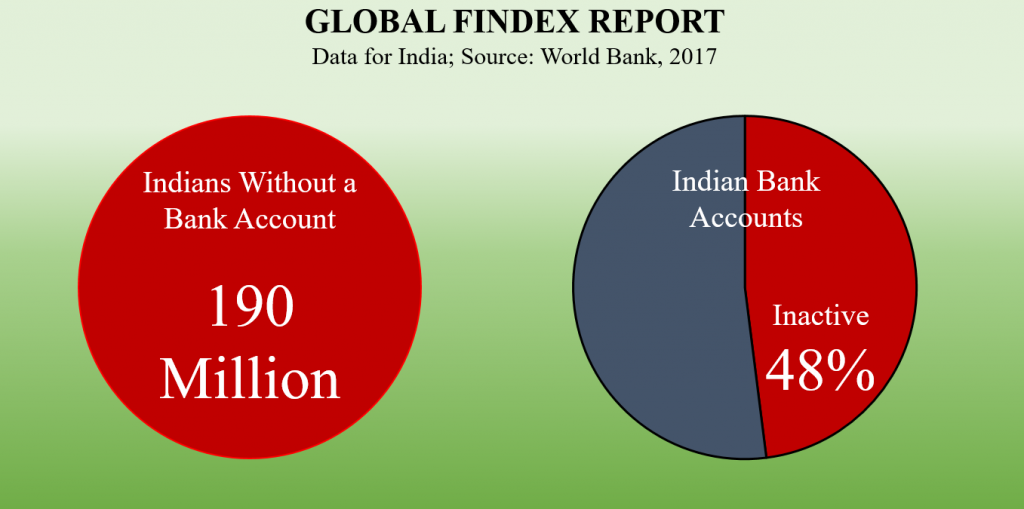

Needless to say, India is still the second largest unbanked population, according to the World Bank Global Findex report – 190 million are without a bank account. What is worse, the percentage of Indian bank accounts that are inactive is 48%: the highest in the world and twice the average of 25% in developing economies. The report attributes part of this malaise to 310 million JDY accounts opened between 2014 and 2018.

The JDY is plagued by charges of misuse, so much so that the RBI itself emphasized that banks need to scrutinize activity in those accounts closely. The RBI cited one of the many examples it found – the account of a daily wage earner in Punjab that saw individual transaction amounts of up to Rs 1 crore. The account holder himself had no knowledge of these transactions in his account.

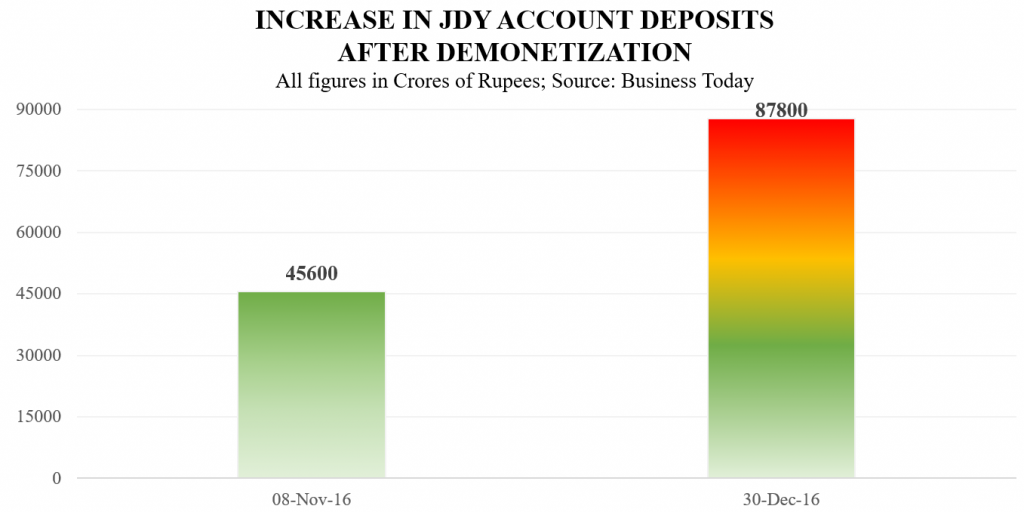

Perversely, the JDY accounts came in quite handy for money launderers who exploited the calamitous demonetization exercise in 2016. Between 8 November when Modi announced it and 30 December, an astonishing 42,200 crore rupees were deposited across 3.74 crore JDY accounts. Total deposits ballooned from Rs 45,600 crore to Rs 87,800 crore, a 92% jump in approximately 2 months. Despite this suspicious activity being flagged by the Central Board of Direct Taxes, the then Finance Secretary, Hasmukh Adhia claimed that these deposits could not be described as illicit.

Equally puzzling data emerged from a query in 2018 under the Right to Information Act – the United Bank of India revealed that the highest balance in an individual JDY account was 93.82 crore rupees. In Bank of India’s case, it was 3.05 crore rupees and for Union Bank, 1.21 crore rupees. In fact the lowest amount reported by any of the nine banks that responded was 4.22 lakh rupees. This contravenes the norms for deposits in JDY accounts – aggregate credit of not more than one lakh rupees a year and a balance of not more than fifty thousand rupees at any given time.

The Delhi police unearthed a racket in which cybercriminals were directing their victims to deposit money into JDY accounts they had opened in the names of people in far-flung remote areas and withdrawing the sums using duplicated thumb impressions.

Inexplicable transactions continue to surface. In February 2020, a woman from Karnataka (who opened the account in 2015 and never operated it) was shocked to discover a balance of Rs 30 crore in her JDY account.

The JDY accounts have been unhelpful even through the COVID19 pandemic. A full 40% of the account holders could not access the relief announced with much fanfare by the Modi government.

The RBI cannot comment on the grandstanding of politicians, only point to the facts and they make for sorry reading. In 2019, as part of their vision paper for payments, the RBI noted that 400 million adult Indians do not have a credit history at all, and a 100 million of these have no bank accounts.

True to Modi’s track record, the JDY has gone the way of numerous other schemes and acronyms over the last six years – initiated by re-branding an existing program (thoughtfully implemented, if not packaged and touted by the UPA government), woeful execution and a series of coercive measures to prove the program an unprecedented success and consigned to the background while some new scheme takes the spotlight over.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. AlignIndia does not take any responsibility for the content of the article.

Santhosh D’Souza combines professional interest in technology with a passion for science, history, mythology and current affairs. He tweets with @santhoshd