In India, the National Education Policy (NEP) was framed in 1986 and later modified in 1992[1]. It is a known fact that education has the power to transform lives. It not only opens doors to better employment; but transfigures the prospects of the poor and marginalized families to build more sustainable and prosperous societies.

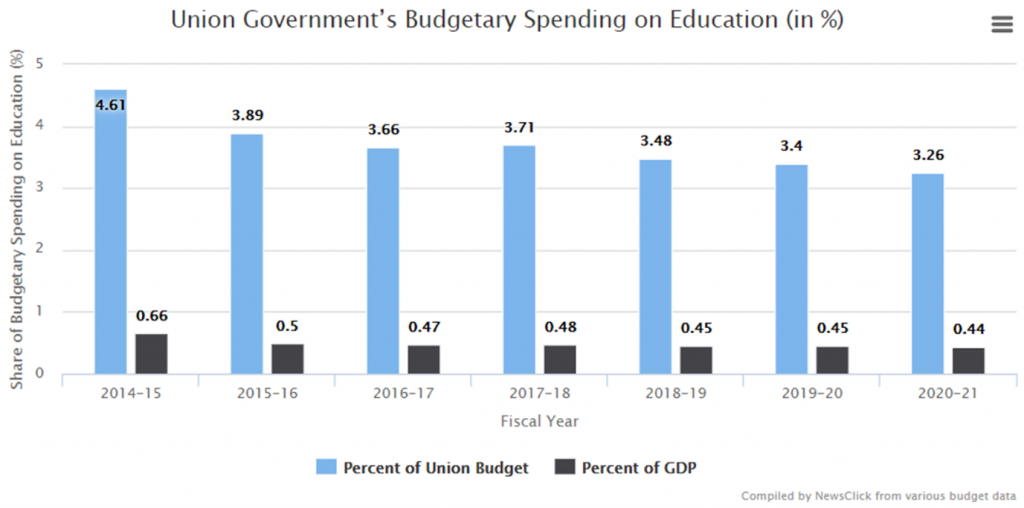

It is notable that in its election manifesto for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had promised that if elected, it would increase India’s spending on education to 6% of the nation’s GDP[2]. The 2014 BJP manifesto said, “Investment in education yields the best dividend. Public spending on education would be raised to 6% of the GDP, and involving the private sector would further enhance this.”[3]

Tragically for the nation, the Union government’s spending on education (as a percentage of GDP) has only seen a constant decline during the six years of the BJP-led government. In fact, there was no mention of the earlier education promise in BJP’s 2019 manifesto for the Lok Sabha elections.

Exhibit 1: The worrying education spend trend

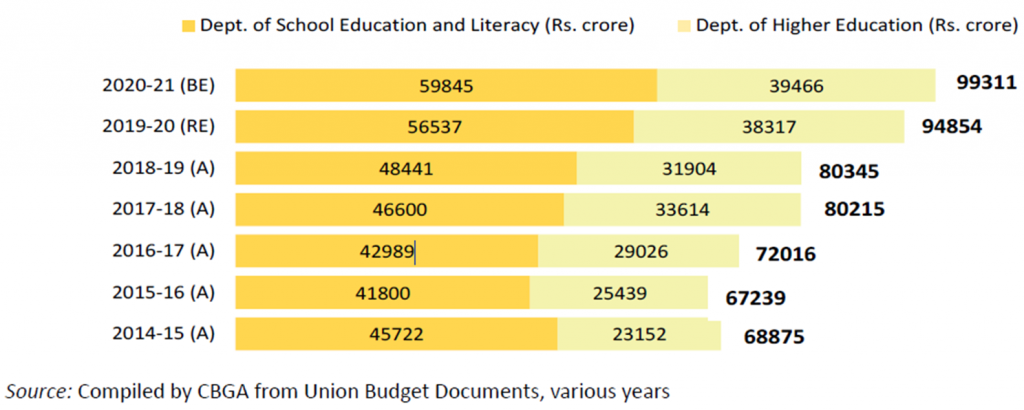

In India’s Union budget for the fiscal year 2020-21, Rs 99,311 crore is allocated to the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). This is an increase of 4.7% from the previous budget. A total of Rs 39,466 crore is allocated to the Department of Higher Education, a rise of 3% from the previous year. Meanwhile the Department of School Education and Literacy is allocated Rs 59,845 crore, a hike of 5.85% YoY.

According to the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA India), though MHRD’s 2020-21 budget has been increased in absolute terms, its proportion in total government expenditure has been continuously falling[4].

Exhibit 2: Department Wise Allocation/Expenditure by MHRD (Rs. crores)

The Indian government released a Draft National Education Policy (DNEP) in June 2019, which reiterated the aim to double education spending to 6% of GDP. It is to be seen whether this will be implemented in practical terms covering multiple areas, including supporting R&D expenditure that is currently at a dismal 0.62% of India’s GDP[5]. What is further worrying is that the nation has a very low human capital base for research, standing at just 0.45% of the students enrolled in higher education[6].

In the 21st century global economy, it is straightforward that shared economic progress and educational outcomes are intimately linked. It is a national imperative to articulate a goal for education and to aim to set higher standards in recruiting and developing teachers. COVID-19’s impact on schooling has also illustrated that smarter online (or digital) systems to gauge student growth and outcomes will be essential to an overall strategy in terms of empowering students through personalized learning experiences via insightful digital content. Supporting Indian students to gain the critically needed skills means boosting national investments in education while simultaneously rethinking teaching and student learning to incorporate customized learning with a cleareyed focus on imparting real-world experiences.

[1] https://mhrd.gov.in/nep-new

[2] https://www.newsclick.in/Union-Budget-FDI-NEP-Privatise-Higher-Education

[3] Ibid.

[4] https://www.cbgaindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Decoding-the-Priorities-An-Analysis-of-Union-Budget-2020-21-1.pdf

[5] https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-many-structural-flaws-in-indias-higher-education-system/article30169923.ece

[6] https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/fixing-higher-education-and-rapid-urbanisation-critical/1799241/